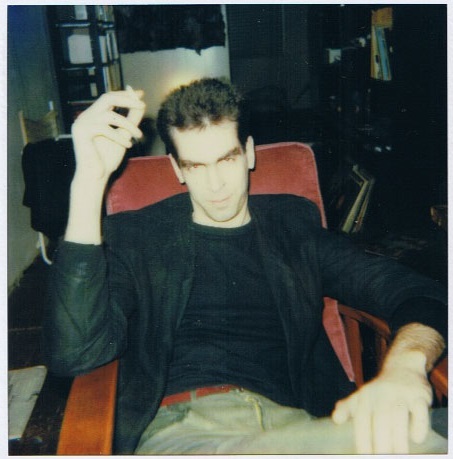

Interview with Dutch artist/publisher Ben Schot (Sea Urchin), specializes in avant-garde and counterculture

By Michalis Limnios | February 11, 2015

“A soundtrack to the Beat Generation: put Allen Ginsberg in a steamy juke joint deep in the Delta in the 1950s, surrounded by Afro-American sharecroppers. Everybody gets drunk, everybody gets stoned, everybody gets naked.”

Ben Schot: Avant-garde Beside The Sea

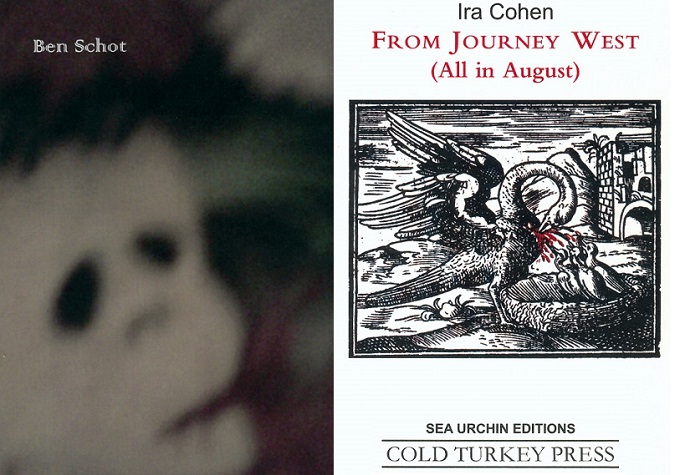

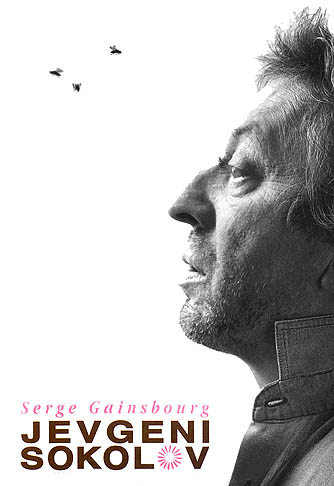

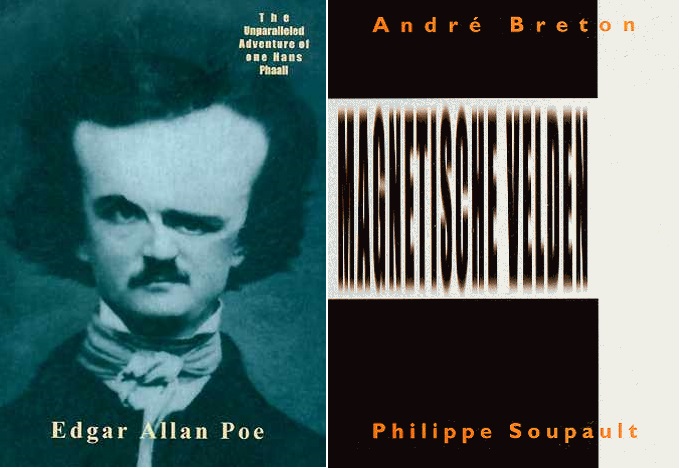

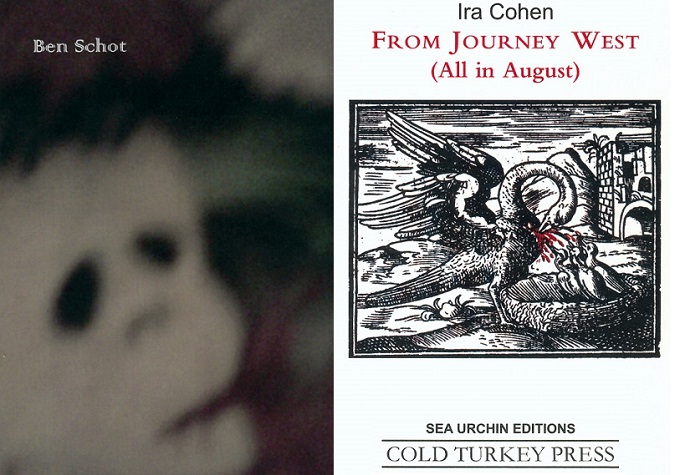

Ben Schot works as an artist, a publisher, and a teacher, and is based in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. His publishing house, SEA URCHIN editions, specializes in works of the historical avant-garde and the counterculture. Sea Urchin publishes both Dutch and English works. Sea Urchin also distributes the editions of a number of other independent publishers and labels from various parts of the world. From 1981 to 1986 Schot was trained as an artist at the art schools of Rotterdam and The Hague. His activities cover various disciplines and techniques: drawings, audio and video works, installation art, and performances. As a writer Schot publishes articles and fiction in various magazines. In 2000 Schot founded the publishing house Sea Urchin Editions which publishes works from the avant-garde and counterculture, such as works by Henri Michaux, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Serge Gainsbourg, Vivian Stanshall & Ki Longfellow, and André Breton. In 2001 Ben Schot produced a free Dutch translation of Cary Loren’s Songs for Holland. Together with Martine Vosmaer Schot translated into Dutch a compilation of Henri Michaux’s hallucinatory prose, which was published by Sea Urchin Editions as Beroofd door de ruimte in 2004. On various occasions Schot gave lectures and presentations on Sun Ra, on whom he wrote an article as well. In 2003 Schot was awarded the Pendrecht Cultuurprijs by Chris Dercon, then director of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Some of the projects that Schot put together are Oulipo (1997) about the French literary movement of the same name, Shells (1997), a project on the museum as an institute at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen Rotterdam, Submerge (1997) on the films of surrealist-biologist Jean Painlevé, Towers Open Fire (1998) on the films of William S. Burroughs, and I rip you, you rip me (1998, in collaboration with Ronald Cornelissen) on the radical and psychedelic counterculture of Detroit in the late sixties, early seventies. As a member of the revolutionary collective The Buggers he staged a Missed Encounter between former Provo leader Roel van Duijn and former chairman of the White Panther Party John Sinclair in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam in 2005. As part of the event Hugh Hopper, Mark Hewins, and Frank van der Kooy were invited by Schot to do a concert at the auditorium of the museum. In 2006 Schot put together an exhibition of material from the archives of the Dutch underground press Cold Turkey Press for the Historical Museum of Rotterdam. In 2008 Schot organized the project Kingdom Come about the notion utopia for the Dutch art institute TENT. The project consisted of an exhibition in which various artists, publishers, and thinkers were invited to react to the concept utopia, a book fair for independent publishers, a discussion with Roel van Duijn, and a performance of the Japanese musicians Yoshida Tatsuya of the band Ruins (band) and Kawabata Makoto of Acid Mothers Temple. On several occasions Schot performed with Dutch electro-acoustic group Kapotte Muziek.

Some of the projects that Schot put together are Oulipo (1997) about the French literary movement of the same name, Shells (1997), a project on the museum as an institute at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen Rotterdam, Submerge (1997) on the films of surrealist-biologist Jean Painlevé, Towers Open Fire (1998) on the films of William S. Burroughs, and I rip you, you rip me (1998, in collaboration with Ronald Cornelissen) on the radical and psychedelic counterculture of Detroit in the late sixties, early seventies. As a member of the revolutionary collective The Buggers he staged a Missed Encounter between former Provo leader Roel van Duijn and former chairman of the White Panther Party John Sinclair in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam in 2005. As part of the event Hugh Hopper, Mark Hewins, and Frank van der Kooy were invited by Schot to do a concert at the auditorium of the museum. In 2006 Schot put together an exhibition of material from the archives of the Dutch underground press Cold Turkey Press for the Historical Museum of Rotterdam. In 2008 Schot organized the project Kingdom Come about the notion utopia for the Dutch art institute TENT. The project consisted of an exhibition in which various artists, publishers, and thinkers were invited to react to the concept utopia, a book fair for independent publishers, a discussion with Roel van Duijn, and a performance of the Japanese musicians Yoshida Tatsuya of the band Ruins (band) and Kawabata Makoto of Acid Mothers Temple. On several occasions Schot performed with Dutch electro-acoustic group Kapotte Muziek.

Interview by Michael Limnios Photos by Ben Schot Archive/All rights reserved

How did the thought behind Sea Urchin start? What characterizes the philosophy and mission of the press?

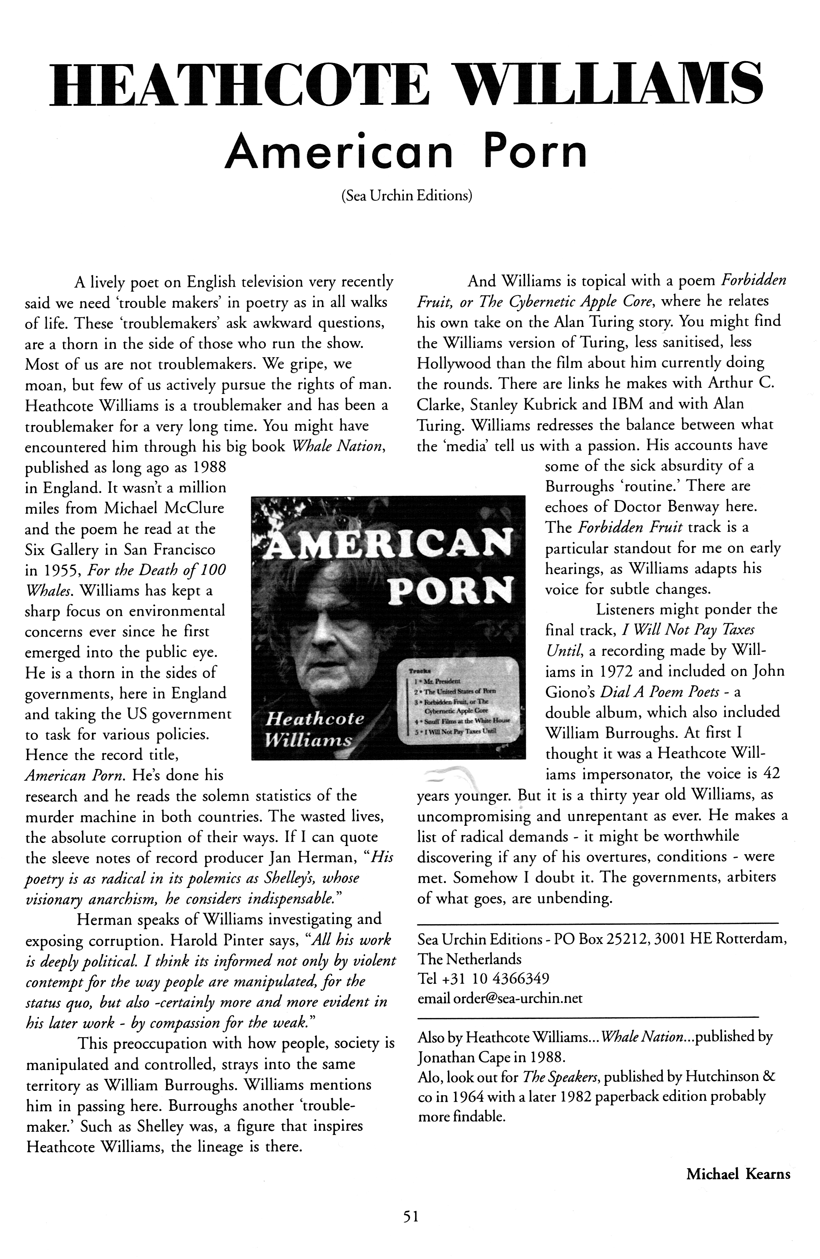

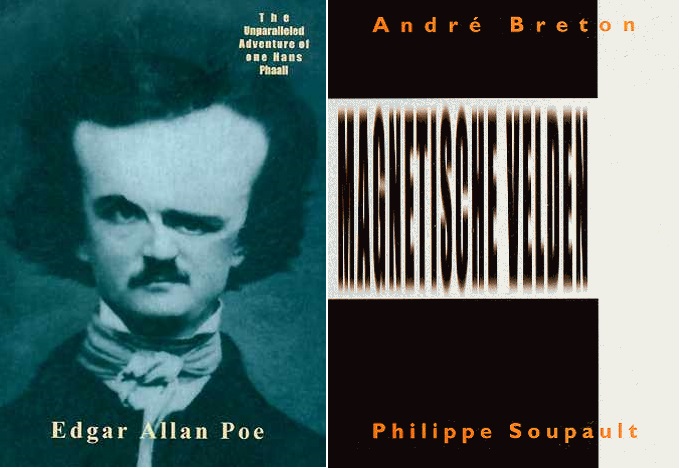

I started making artists’ books at art school and continued to do so – on a very small scale – in the 1980s and 1990s, at first they were xeroxed editions of 5 or 10 copies, later larger offset printed artists’ books. The books were combinations of texts, drawings, photos and found images. I used fictitious imprints to publish those. When I came across a tale by Edgar Allan Poe that was set in Rotterdam, I published it under a new imprint: Sea Urchin Editions in 2000. I chose the name Sea Urchin as a reference to my youth in Zeeland, where my father made a living as a fisherman and as an homage to Jean Painlevé’s ‘Oursins’, which is a hallucinatory, surrealist film about sea urchins.

Sea Urchin doesn’t really have a philosophy or mission, but it focuses on works from the counterculture, avantgarde and their predecessors. It’s a long historical line of rebellion, subversion and perversion that I’m interested in. I feel at home there. As a 13-year-old kid I watched The Who smash their instruments on TV and saw Dutch Provos undermining authority and provoking the police into actions that exposed them as fascistoid pigs. Everything was in uproar and up in the air in those days. The mid-1960s were electrifying days, especially for a kid my age, who had his own personal rebellion to deal with at home.

In the early 1970s (I was 17-18 years old by then) I used to hang out in an alternative café that people from Rotterdam had started in the small countrytown where I lived. They created a meeting place for pacifists, socialists, communists, anarchists, artists, musicians, and local freaks like me, showed art and screened films by Godard, Pasolini, Antonioni and many others. In that café you could find Albert Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus lying on the table next to European underground magazines such as ‘Suck’ and you could listen to the latest music high on hashish or tripping on acid. The café, film screenings, music, literature and people there were a great source of inspiration. So was a school trip to a big Dali exhibition in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam in 1970. It blew my mind and helped me decide to become an artist. Only later did I understand that The Who’s destruction of their instruments was inspired by Gustav Metzger’s auto-destructive art, that the Provo happenings were connected to the Situationists, that the Bonzo Dog Band took inspiration from the Dadaists, that the cut-ups that Burroughs and Gysin claimed to have discovered were in fact an old dadaist technique, and that there were all sorts of links between the music, films, art and literature that I loved and the historical avant-garde and their 19th-century predecessors. Those historical lines continue to fascinate me to this day and it’s that fascination that lies at the heart of Sea Urchin. I still discover something new almost every day.

In the early 1970s (I was 17-18 years old by then) I used to hang out in an alternative café that people from Rotterdam had started in the small countrytown where I lived. They created a meeting place for pacifists, socialists, communists, anarchists, artists, musicians, and local freaks like me, showed art and screened films by Godard, Pasolini, Antonioni and many others. In that café you could find Albert Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus lying on the table next to European underground magazines such as ‘Suck’ and you could listen to the latest music high on hashish or tripping on acid. The café, film screenings, music, literature and people there were a great source of inspiration. So was a school trip to a big Dali exhibition in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam in 1970. It blew my mind and helped me decide to become an artist. Only later did I understand that The Who’s destruction of their instruments was inspired by Gustav Metzger’s auto-destructive art, that the Provo happenings were connected to the Situationists, that the Bonzo Dog Band took inspiration from the Dadaists, that the cut-ups that Burroughs and Gysin claimed to have discovered were in fact an old dadaist technique, and that there were all sorts of links between the music, films, art and literature that I loved and the historical avant-garde and their 19th-century predecessors. Those historical lines continue to fascinate me to this day and it’s that fascination that lies at the heart of Sea Urchin. I still discover something new almost every day.

How do you describe Ben Schot’s artwork? What experiences have triggered your ideas most frequently?

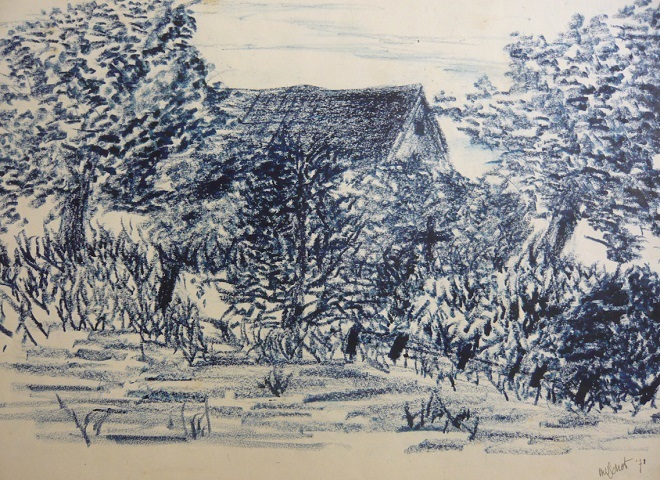

I have always liked drawing and I still think of myself as primarily a draughtsman. It is the most natural art discipline for me. But I certainly couldn’t make drawings on on a daily basis like some artists do. Or make series of thematically or stylistically consistent drawings. I’m too restless for that. Consistency, style and strict concepts are boring slave masters. I have to free myself from them (and never stop ridding myself of them, because they will always creep up on you rattling their cosy balls and chains). For that reason I believe my work always contains a destructive element. That is certainly true of my drawings, which frequently start with the destruction of an older drawing or picking up a drawing I had rejected earlier. Destruction or embracing rejected works is often my first step in the process of drawing. That’s something I learnt from Krijn Giezen, a Dutch artist who used to be one of my teachers in art school. And… you have to let chance in. That’s something I learnt not only from Krijn Giezen but also from the dadaists, surrealists, Dutch Provos and improvisational musicians. You have to let chance in somehow. The whole idea is to open up your work to something you DON’T control.

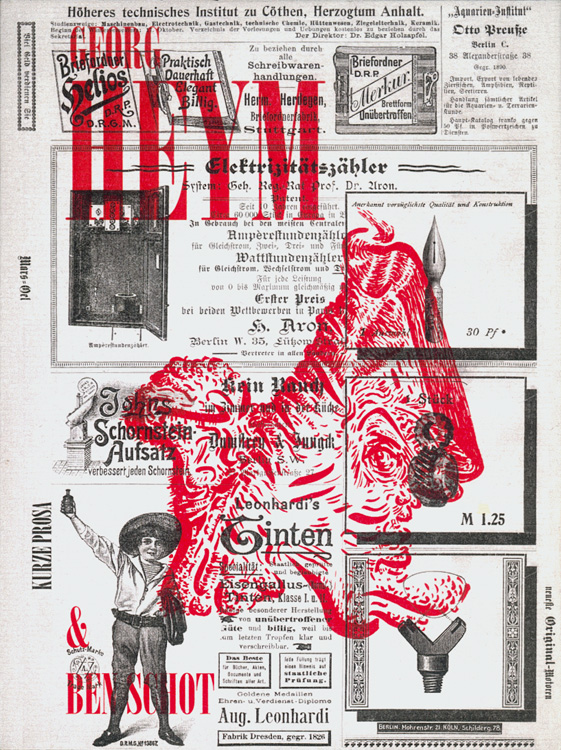

I like vandalic techniques too. They are a very refreshing kind of violence and perversion. Vandalism is a subversive and powerful tool in exposing false images. Kids use it instinctively. But it can be applied more consciously too, of course. I started Dämmer Magazine in 2008 as an experiment in classic vandalic techniques. I still do a Dämmer cover every now and then: whenever I feel the need to react to a political, social or cultural issue, which is not as often as I used to. Some people love them, others hate them. They’re all done fast. Vandalism works best when it’s done before the esthetic and ethic cops have the chance to arrive.

Drawing comes naturally but making books too. Making books and starting Sea Urchin was a logical extension of my artist’s practice and it still is. My work is not all about violence and destruction, of course. I think of beauty as a very powerful force too. I’m a sucker for beauty. It’s a way of getting out of here. Maybe that’s what triggers my ideas most of all: finding the exit and a doorway out of here.

“For the postwar generation that I was part of the term ‘underground’ had all sorts of associations with the resistance groups of World War II. It had a romantic and heroic ring to it. It provided partisan credibility.”

How important was music in your life? How does music affect your mood and inspiration?

Music has been important to me since the late 1950s-early 1960s. Before that there were only boring Dutch pop songs on the radio, even more boring hymns in church, and the soporific Mantovani LP that my mother used to play at home. They were all REPRESSIVE kinds of music, either meant to make you consume, calm you down, or bore you for eternity. But then my sister, who is ten years older than I, brought home a taste of rock ‘n’ roll: Elvis, Little Richard, Bill Haley, greaser friends, petticoats, parties, dances. I couldn’t quite identify with that music – I was just a kid and this was music for horny young adults – but I understood and loved the energy, the excitement and the sense of DANGER that it aroused. The first pieces of music that I could really identify with were songs by The Beatles. Shortly after that The Stones, The Kinks, The Who. That must have been 1963-1965. That music made me feel part of a generation of kids who felt the same way I did, a new generation that was about to kick out the boring old one and shake off their repressive yoke. It told us something was in the air. Something good. Something dangerous.

My friends and I listened to music whenever we could in the second half of the 1960s. Radio stations tuned in on kids my age, who were a booming market, and we bought our own singles and LPs if we could afford them. I remember hearing ‘Wild Thing’ by The Troggs when it came out on the radio in 1966 and thinking to myself: ‘that’s the most exciting piece of music I’ve ever heard ‘. Then came The Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd ( I smoked my first joint listening to Pink Floyd’s first album), Soft Machine, Captain Beefheart, Frank Zappa, Hawkwind, the works (although a lot of great psychedelic music never reached us in those days. Not where I was living). We smoked hash and dropped acid listening to Pink Floyd’s ‘Umma Gumma’, Hawkwind’s first album, and Dr. John’s ‘Gris-Gris’. They propelled us into other worlds. And that was exactly where we wanted to be.

I’ve been exposed and open to all sorts of music since then. I still listen to psychedelic music and (punk) rock but prefer free jazz nowadays. I listen to electronic music, noise, anything except classical music that I find hard to get into. I know artists who couldn’t work with music playing in their studio but I would find it hard to work without it (except when I’m writing; that’s the only time when I can’t bear music). Music is an energy, a vehicle, a spaceship to another world as Sun Ra would put it. Either that or a healthy punch in the kisser to knock some sense into you.

“So what does underground literature look or sound like nowadays? I know what it used to be but couldn’t tell what it is nowadays. Jihadist rants? Charlie Hebdo? Mein Kampf? And does being underground make them good literature? I don’t think so. ‘Underground’… Personally, I’d like to stay above ground as long as possible and wait a while before pushing up the daisies.”

What has been the relationship between music, literature, visual art (..and comics) in your life?

Well, I think I have already answered most of that question, at least as far as music and visual art are concerned. Comics have never really been my thing. I mean, of course I used to read comics as a kid (I even wrote letters to Donald Duck and got replies too) and, yes certainly, later I would laugh my head off at the comics that you would find in ‘underground’ magazines in the 1960s and 1970s: Robert Crumb, The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, Wolinski, Reiser, Herman Brood, etc., but I was not really into them and I don’t remember ever having collected comic books or zines.

I liked to read boys’ adventure books as a young kid and was into SF, horror and detectives as a 14 to 15-year-old: Michael Moorcock, H.P. Lovecraft, Edgar Allan Poe, Havank, Ian Fleming. At secondary school I was introduced to modern Dutch literature and some English, French and German literature, but I’m afraid most of it was wasted on me at the time. My Dutch literature teacher was a reasonably well-known Dutch poet, inspiring to most pupils but not to me. His flaunting poetry and forcing it down pupils’ throats turned me off completely. We didn’t like each other. I remember having written a short SF story as an interpretation of one of his assignments when I was some 16 years old. He returned it to me with a low grade and the remark that it must have sprung from a ‘really sick and disturbed mind’. I was lost on him and most of his teachings were lost on me. I preferred listening to my English teacher, a pockmarked former sea-faring sailor who drank heavily, smoked cigarettes in the classroom and wrote Beatles lyrics on the blackboard for his students to translate and analyse. I didn’t get into serious literature until I had left secondary school.

After I had graduated from secondary school I wanted to enter art school, but I wasn’t admitted and then was drafted for military service. I refused to do that service. I started studying English Language & Literature at home during the extremely long procedure you had to go through as a conscientious objector in those days. They gave you the hardest and longest possible time if you refused military service. I read a lot in those years, not only old and modern English literature but also Camus, Sartre, Nietzsche, Freud and Dutch literature, which I was finally able to enjoy. Literature has been a source of inspiration since then. After I had finished my alternative military service (all in all the procedure had taken some five years) and had been admitted to art school, literature and theoretical writings were an important stimulus in my development as a visual artist, more so than music. They still are. Words fire the imagination and looking into the mechanisms of language means laying bare the inner workings of our psyche and culture. Let’s not forget that the surrealists were primarily a literary movement, so were the lettrists and situationists. The counterculture and avant-garde were to a large extent shaped by words and cracking open language. I’ve always been more into prose than into poetry, though, but that’s just a matter of taste.

“Sea Urchin doesn’t really have a philosophy or mission, but it focuses on works from the counterculture, avantgarde and their predecessors. It’s a long historical line of rebellion, subversion and perversion that I’m interested in. I feel at home there.”

You have come to know great personalities. Which meetings have been the most important experiences for you?

True, I’ve met some great people over the years but I don’t really know if you can call those meetings – or the acquaintances and friendships that have evolved from some of those – ‘important’. Time will tell. And then, of course, there are people not very well-known or not known at all, who have been very important in my life. Being great and being important are not synonymous. My girls, Anneke and Puck, are important to me. And, yes, I’m fortunate to have a couple of generous and inspiring friends. I’m a rich man.

What did you learn about yourself from the counterculture and what does underground literature mean to you?

The ‘counterculture’ is a term invented by the academic Theodore Roszak to categorize various subcultures, civil rights and anti-war movements of the late 1960s. I don’t think I heard the term until much later. Anyway, the late 1960s-early 1970s were an era that coincided with my puberty and adolescence. I had a lot to rebel against and get away from at home. As a result of that I gravitated naturally towards various exponents of the ‘counterculture’: music, drugs, pacifism, art, literature. Other exponents didn’t appeal to me at all: orientalism, mysticism, back to nature stuff. Nor did I get very deep into politics – even though I was a conscientious objector to military service. But I was certainly attracted to the rebellious and subversive aspects of what Roszak labelled ‘counterculture’.

I don’t think the counterculture itself taught me much, but its failure certainly did. The counterculture was only fresh for a couple of years. Then it collapsed under its own weight due to internal rot and fermenting complacency in its construction. Its downfall taught me a lot about the mechanisms and strategies of consumer societies, about repressive tolerance, about commodification, about selling out. The counterculture was eaten, digested and shat back into our faces by the consumer societies. It was weak. I learnt a lot more from Dada and Freud. To my mind those have remained vital forces: I still draw inspiration from them. Revolt, anarchism and the subconscious: powerful food for any countercultural pupa. Fat moth meat to be grilled in the light.

For the postwar generation that I was part of the term ‘underground’ had all sorts of associations with the resistance groups of World War II. It had a romantic and heroic ring to it. It provided partisan credibility. The term ‘underground’ was already dubious in the 1960s and 1970s, but is even more so today. It’s become a label, a hallmark that helps market and sell commodities. I feel we should restore some of the original power to the term and do justice to those people and works that are or were really underground. John Sinclair did time in prison for what he wrote, said and thought, so did Timothy Leary (whatever you may think of him). There were Black Panthers, The Weather Underground, The German RAF. All underground. John Cleland wrote ‘Fanny Hill’ in prison and was re-imprisoned after its publication. There were Robert Desnos and De Sade, Czech Charter 77 writers, all part of a long line of true ‘underground’ writers all over the world who posed a threat to the establishment serious enough to have them put away. Because you don’t go underground voluntarily; you are FORCED underground because what you do is against the law. If you want to call yourself underground you‘d better start writing and publishing as if you are already being drawn and quartered by invisible horses.

For the postwar generation that I was part of the term ‘underground’ had all sorts of associations with the resistance groups of World War II. It had a romantic and heroic ring to it. It provided partisan credibility. The term ‘underground’ was already dubious in the 1960s and 1970s, but is even more so today. It’s become a label, a hallmark that helps market and sell commodities. I feel we should restore some of the original power to the term and do justice to those people and works that are or were really underground. John Sinclair did time in prison for what he wrote, said and thought, so did Timothy Leary (whatever you may think of him). There were Black Panthers, The Weather Underground, The German RAF. All underground. John Cleland wrote ‘Fanny Hill’ in prison and was re-imprisoned after its publication. There were Robert Desnos and De Sade, Czech Charter 77 writers, all part of a long line of true ‘underground’ writers all over the world who posed a threat to the establishment serious enough to have them put away. Because you don’t go underground voluntarily; you are FORCED underground because what you do is against the law. If you want to call yourself underground you‘d better start writing and publishing as if you are already being drawn and quartered by invisible horses.

So what does underground literature look or sound like nowadays? I know what it used to be but couldn’t tell what it is nowadays. Jihadist rants? Charlie Hebdo? Mein Kampf? And does being underground make them good literature? I don’t think so. ‘Underground’… Personally, I’d like to stay above ground as long as possible and wait a while before pushing up the daisies.

What do you miss most nowadays from the past? What are your hopes and fears for the future?

There is very little I miss from the past. On the whole I’m happy where I am now. But sometimes I miss the landscapes from my youth: the dunes, the sea, the dikes, the wind and the skies, the smell of honeysuckle, the call of an oystercatcher. They are all imprinted in my soul. Sometimes I drive south to the island where I grew up to feed my soul on the landscapes there for a day and then drive back to Rotterdam. I couldn’t live on the island any more but I’m glad I can still go there every now and then and get in touch with my roots.

I’m not the most optimistic guy when it comes to mankind, so my hopes of a better world are pretty slim. I’ve always been more of a survivor than an idealist to begin with and what ideals I had when I was young have evaporated in the course of time. Unless we get rid of the caste of usurers and warmongers that keep the planet in a stranglehold, nothing is going to change. It will take a lot of force to kick them out. They hold the trumps and have the guns.

But I do believe in art, music, literature, beauty, love and imagination. Mankind is at its best there and manages every now and then to build sublime vehicles that have the power to transport you away from here, even to transcend death. If there is hope for mankind then surely we should look for it in those areas. To another world, brothers and sisters!

“I have always liked drawing and I still think of myself as primarily a draughtsman. It is the most natural art discipline for me. But I certainly couldn’t make drawings on on a daily basis like some artists do. Or make series of thematically or stylistically consistent drawings.”

Why are the blues and jazz connected with the Beats and what characterizes the soundtrack of the Beat generation?

That’s a difficult question, all the more since I don’t know enough about either the blues, jazz or the Beats. Like most people my age, the blues first reached me through covers of blues songs by European sixties bands: The Stones, John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers, Q65, Cuby & The Blizzards. Willie Dixon was a name you came across when you read the credits to some of their songs, but I had no idea who he was until much later. John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf, and Muddy Waters records you would find at friends’ places, but they usually belonged to the father or an older brother. We listened to other stuff. We were too young for the Blues. Only when the Blues came to us wrapped in sexy, young white men instead of old black guys did it appeal to us in the 1960s and 1970s. We were in the middle of a generational conflict. I only began to fully appreciate the Blues when I heard John Lee Hooker’s ‘I’m Going Upstairs’ and that was, I think, in the mid-seventies. The Blues is an acquired taste, it has to grow on you, like wild lichen that comes with age. Now I listen to the Blues a lot. And there’s so much great music available and so much still to be discovered. The Blues. ‘How long you been dead?’ (Bukka White).

Jazz also reached me through white bands like Soft Machine and the Dutch band Supersister, who I used to hang out with when they came down to the island where I lived. They sort of opened up that field of music for me as a kid. I remember seeing Sun Ra and The Archestra on Dutch TV in the early 1970s and being blown away by their performances. Rotterdam still had a couple of good jazz venues when I moved there. I went there every now and then but it wasn’t really my scene. Cary Loren pointed out to me a whole spectrum of ecstatic jazz. Now I’m mostly into free jazz, but am also discovering other forms of jazz.

How’s this for a soundtrack to the Beat Generation: put Allen Ginsberg in a steamy juke joint deep in the Delta in the 1950s, surrounded by Afro-American sharecroppers. Everybody gets drunk, everybody gets stoned, everybody gets naked. The local band begins to play. Everybody dances. Ginsberg trips out and fires rounds of free verse on the spot. Then Burroughs, impeccably dressed, opens the door.

“There is very little I miss from the past. On the whole I’m happy where I am now. But sometimes I miss the landscapes from my youth: the dunes, the sea, the dikes, the wind and the skies, the smell of honeysuckle, the call of an oystercatcher. They are all imprinted in my soul.”

Which is the moment that you change your life most? Which has been the most interesting period in your life?

The summer of 1969: A thunderstorm is about to break. The sky is Napels yellow and black. All is lost. All is erased. Even the memory of this day.

If you could change one thing in the world and it would become a reality, what would that be?

This question is truly daunting in its magnitude. Every change that comes to mind seems to have more disadvantages than advantages. And answering it is too big a responsibility for me. I’ll have to talk to my lawyer first.

What is the best advice ever given you?

The best piece of advice I ever got was not to share my memories without due warning.

Where would you really want to go with a time machine and what books, records, etc. would you put in?

Where would you really want to go with a time machine and what books, records, etc. would you put in?

I’m not much of a traveler but when I do travel I like to do it as light as possible. No books, no records, thank you. I’ve been carrying those around too often as a publisher. Because of curiosity I’d like to take a peek in the relatively near future, let’s say 100 years from now. I’m not sure that would be a time I look forward going to, though. But it would teach us a thing or two. It’s a romantic notion but I think that I would like to roam the 19th and 20th century leisurely on the H.G. Wells Xpress, making stops at will. I wouldn’t go anywhere without a return ticket, though.

Original article by Michalis Limnios on Blues@Greece

‘Of dit boek enige weerklank zal vinden betwijfel ik ondanks het vriendelijke (onleesbaar woord). Want het is niet voor een tijd geschreven die charlatans voor dichters houdt, die onder elkaar een verzekering op wederzijdse welwillendheid hebben afgesloten’, schrijft Georg Heym in het voorwoord van het boek Kurze Prosa uitgegeven door Moloko Print. Heym was een Duitse schrijver van proza, toneelstukken en gedichten die weliswaar op jonge leeftijd stierf maar toch van aanzienlijk invloed op degenen na hem was. Hij wordt gezien als de wegbereider van het literaire expressionisme.

‘Of dit boek enige weerklank zal vinden betwijfel ik ondanks het vriendelijke (onleesbaar woord). Want het is niet voor een tijd geschreven die charlatans voor dichters houdt, die onder elkaar een verzekering op wederzijdse welwillendheid hebben afgesloten’, schrijft Georg Heym in het voorwoord van het boek Kurze Prosa uitgegeven door Moloko Print. Heym was een Duitse schrijver van proza, toneelstukken en gedichten die weliswaar op jonge leeftijd stierf maar toch van aanzienlijk invloed op degenen na hem was. Hij wordt gezien als de wegbereider van het literaire expressionisme.